Jacobs has operated the City of Vancouver’s wastewater utilities since 2016 and delivered engineering and technical services to the City for over 20 years. For almost the same amount of time Jacobs has worked for Vancouver—nearly two decades—consumers have been sold flushable wipes. But flushable does not translate to digestible. Frank Dick, engineer for the City of Vancouver, Wash., and a Jacobs client, is gaining ground with legislation and manufacturers alike to help reduce clogs in U.S. sewers.

“It seemed baby wipes started to become extremely popular in the 1980s and ‘90s, but it wasn’t until the early 2000s when personal hygiene ‘flushable wipes’ started to gain popularity with consumers,” explains Frank. “At the time, these flushable wipes were simply smaller-sized, over-priced baby wipes, and the packaging did not differentiate between flushable and non-flushable.”

Based on Frank’s and others’ observations, uninformed consumers opted for the cheaper option: baby wipes, which are just as clog prone as most flushable wipes, leading to an abundance of regularly clogged sewers and wastewater treatment systems across the nation and globe.

Global collaboration and innovation

While the needle is slowly moving in the favor of the U.S.’ wastewater industry, they’re far from alone in this journey.

As of 2016, representatives from the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan and Spain work together to dissolve the notion that flushing wipes is OK, and they created a criterion for flushability and test methods. Over 300 entities world-wide signed onto a flushability statement back in 2016.

“In 2016, the U.S. contingent of wastewater—with the support of NACWA and WEF—joined water organizations from other countries around the world to form the International Water Services Flushability Group,” says Frank. “The group developed a set of specifications for flushability that government agencies could use to establish regulations regarding products used in toilet settings.”

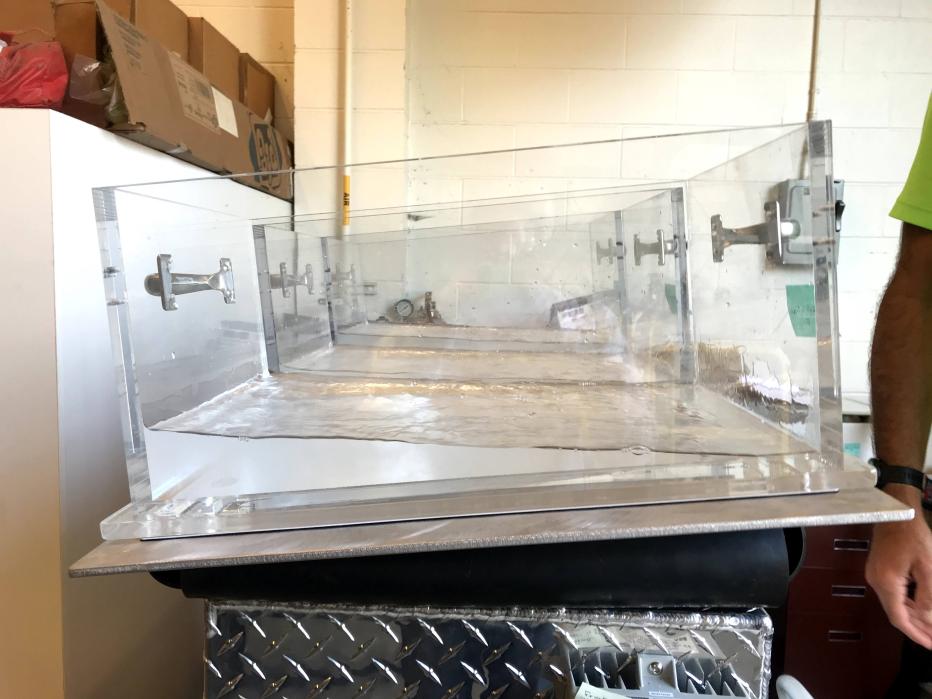

Slosh box testing

After years in the industry and extensive observation, Frank and his team saw how wipes continued to damage pumping equipment and clog Vancouver’s treatment systems. Collaborating with the other members of the International Water Services Flushability Group, Frank and his colleagues took to science and testing to prove how toilet paper (and not wipes whether flushable or not) should be truly be the only paper substance flushed down a toilet. As a result, they took to the slosh box—a testing procedure introduced by the International Nonwovens and Disposables Association (INDA).

The slosh box creates a bench test to determine ability for a wipe—and other items—to disintegrate in water conditions similar to wastewater treatment systems. The idea approximated conditions in a sewer for hydraulic and mechanical forces to break apart wipes.

And the team’s findings? Minor toilet paper debris; significant flushable wipe remanence and nearly full, intact baby wipes.

Working with manufacturers

With data and examples in hand, Costco’s headquarters located in Seattle and Frank just up the road in Vancouver, he managed to get in front of Costco’s top executives, present his findings and formally request they remove the word flushable from their Kirkland (Costco-brand) baby wipes packaging. Costco took his request serious, and not long after Kirkland-brand baby wipes had prominent and visible do-not-flush labels on packaging and boxes.

“Kudos to Costco,” adds Frank. “They were one of the first companies to take the lead on this and make the do-not-flush label larger and more noticeable on packaging.”

INDA simultaneously adopted the Code of Practice developed from its wastewater collaboration, which calls for more-visible labeling of a Do-Not-Flush logo to be placed on the front sides of packaging that faces consumers on store shelves. This Code of Practice was published, and unfortunately compliance has been spotty.

“With the new legislature in Washington, Oregon, California and Illinois going into effect soon—along with the effort being put forth by manufacturers such as Kimberly-Clark, I have high hopes that these wipes truly will be considered not only flushable but also digestible in the future. Our water and wastewater infrastructure depend on it.”

From legislation to lawsuits

Frank’s dedication to help solve this predicament led him to testify in front of Washington legislature and work with local Washington legislators to change how manufacturers promote wipes. Frank and several others spoke in front of the Washington House Committee on the Environment.

“In 2019 a wastewater backup caused by wipes closed a popular Seattle beach, and the leader of this Washington environmental committee decided to take action,” says Frank. “This event was the impetus to get legislation moving.”

While getting new legislation passed to keep sewage systems wipe-free has been slow and arduous, other legal actions have yielded more immediate results. Recently, the Charleston Water System in South Carolina filed a class-action lawsuit against flushable wipe manufacturers, including Costco, CVS, Kimberly-Clark Corp., Procter & Gamble, Target, Walgreens and Wal-Mart.

Kimberly-Clark—the manufacturer that produces household names like Scott and Cottonelle, did not accept wrongdoing and agreed to a settlement in spring 2021 that included all owners and operators of wastewater conveyance systems across the U.S.

The overall result worked in favor of U.S. cities and counties that own or operate wastewater treatment plants, as Kimberly-Clark took initiative to update labeling and complete two years of testing to improve flushability. Kimberly-Clark is now leading the way among U.S. manufacturers regarding flushable wipes. The company is altering its patented technology to permit flushable wipes to break down easier and help reduce clogs.

Looking forward

While the calamity of unclogging wastewater systems is far from over, Frank is doing his part—along with other entities locally and abroad—to help enlighten consumers, manufacturers, retailers and agencies about the reality of flushable wipes.

“With the new legislature in Washington, Oregon, California and Illinois going into effect soon—along with the effort being put forth by manufacturers such as Kimberly-Clark, I have high hopes that these wipes truly will be considered not only flushable but also digestible in the future,” says Frank. “Our water and wastewater infrastructure depend on it.”

Wipes vs. toilet paper

So, with all of this, what’s the difference between a baby wipe, a flushable wipe and toilet paper? A lot, actually.

Baby wipes are straight up made from plastic and are highly unlikely to disintegrate in water. These should never be flushed.

Most of the content in flushable wipes is cellulose (pulp fibers found in toilet paper). However, to give strength to these wipes while in the package and during use on a toilet, longer fibers are embedded in the material. All these fibers go through special processes—such as spunlace and hydroentanglement—to produce strong, non-woven materials.

And toilet paper is made up of cellulose short fibers from wood and plants. Without plastic additives, toilet paper breaks down easier and leads to significantly less clogging in sump pumps, septic tanks and wastewater treatment processes.

Clearing clogs—manually

How are flushable wipe clogs cleared? Manually, unfortunately. Operators have to reach into pumps and use tools to break up the clogged materials.

.jpg?h=c7c14dee&itok=FmPI2126)

_0.jpg?h=8a6d63f3&itok=5vsqFiQH)

.png?h=1314d3d4&itok=rFs9mG95)